Remembering Eileen Kaufman

by John Geluardi

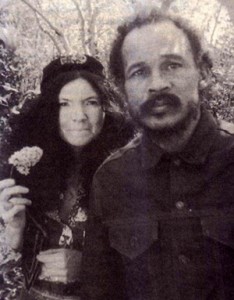

Poet, musician, editor and journalist Eileen Kaufman died last month in Richmond, California where she had lived for the past five years. Kaufman led an interesting and varied life that included a career in the Navy during World War II, working as a car saleswoman and a rock and roll journalist. But Kaufman is perhaps best known for being the wife, editor and champion of poet Bob Kaufman whose internationally renowned poetry may have easily slipped into obscurity had it not been for Eileen’s relentless belief in the importance of his work. Eileen was 93.

Eileen Singe was born and raised in the South. She joined the Navy during World War II and was stationed at Pearl Harbor where she primarily worked in Navy public relations. According to her son, Parker, the public relations work sharpened her writing skills and one of her duties was pinning medals onto the uniforms of Navy officers who had distinguished themselves in battle.

After retiring from the Navy, Eileen settled in the Sacramento area where she married and had a daughter, Lisa. During those years, she raised her family and worked as a car saleswoman. However, by the late 1950s, the marriage had failed and Eileen, who always had a strong interest in the arts, was drawn to the Beat literary movement in San Francisco. With her raven black hair, piercing eyes and winsome manner, Eileen was natural fit in the then thriving North Beach art scene.

Eileen met Bob Kaufman late one night in 1958 at a friend’s North Beach apartment. It was 3 a.m. and Bob showed up wanting some coffee. She agreed to accompany him to the all-night Hot Dog Palace where they talked for hours and within a month, they were married in Mexico. “I was overwhelmed when I met Bob,” Eileen said in 1996 interview. “After that first night, he said to me, ‘You are my woman. You have no choice in the matter.’ He was right.”

Eileen fully embraced the Bohemian lifestyle and she and Bob quickly became central figures in North Beach’s art scene. In 1958, she helped Bob co-found and edit Beatitudes magazine, which was dedicated to publishing unknown poets. The magazine provided a platform for many highly respected poets who were at the time largely unknown such as Richard Brautigan, Michael McClure, Ruth Weiss, Jack Micheline and Kirby Doyle. The first incarnation of the magazine only published 17 issues, but has had a lasting impact on the Beat literary movement nationally.

But life with Bob was not easy. In 1959, the couple had a son, Parker, who was named after jazz great Charlie Parker. Creating a harmonious family life was a challenge because of Bob’s heavy drinking, drug use and near constant run-ins with the police. He was arrested with such frequency that many North Beach bars and cafes kept contribution jars handy that read “Bob Kaufman bail fund.”

Bob, who was half black and half Jewish, was often targeted by police because he was married to Eileen who was white and because they had an interracial child. “People take that for granted now, but in the late 1950s people, not just the police, saw their relationship as a threat to the social order,” said Raymond Foye, who edited Kaufman’s 1981 poetry volume The Ancient Rain.

Bob was a unique poet in that he did not always write down his poems. He also keep no journals, wrote no literary essays, and maintained no correspondence. Instead, he presented his poems orally and spontaneously in bars, cafes and on the hoods of cars in North Beach. “Adapting the harmonic complexities and spontaneous invention of the be-bop to poetic euphony and meter, he became the quintessential jazz poet,” Foye wrote in the introduction to The Ancient Rain.

Many of Bob’s poems may have never reached print had not Eileen been diligent about transcribing his oral verse. “She is responsible, by and large, for Bob being published,” Foye said. “She preserved his poems by writing them down sometimes on bar napkins, matchbooks and paper sacks. In fact, Bob’s 1965 poetry volume Solitudes Crowded with Loneliness, is really her work editorially.”

Eileen talked about supporting Bob’s work in a 1996 interview with the San Francisco Chronicle. “I think every artist needs someone like that in their life,” Eileen said. “I was the one who talked to the publishers. He had no patience or gift for that. With Bob, it was clear to me that this man was a genius. I was glad to stand behind him.”

In 1960, Eileen and two-year-old Parker followed Bob to the East Coast where he had been invited to read at Harvard. But instead, they wound up in New York where family life became more complicated by Bob’s heavy drug use and abject poverty. Eventually, Eileen returned to San Francisco with Parker and Bob remained in New York. By the time he returned to San Francisco, he was a different man. In New York, he had been repeatedly arrested and at one point sent to Bellevue Hospital where they shaved his head and subjected him to involuntary shock treatment. One week after his return to North Beach, President John Kennedy was killed and Bob was so shaken by the assassination that he took a monk-like vow of silence that lasted 10 years.

Eileen took Parker to Mexico where she readied Solitudes Crowded with Loneliness, for publication. After returning to the states, she worked as a journalist writing early stories about The Grateful Dead, The Doors, Janis Joplin and Jimi Hendrix. Her articles appeared in the Los Angeles Free Press, the Los Angeles Oracle, Billboard magazine and Music World Countdown.

In the early 1970s, Eileen headed to Europe with Parker. Over the course of four years, mother and son spent time in Spain, Morocco and Afghanistan.

After returning to the states, Eileen remained close to Bob and the two reunited briefly in the mid-1970s. The couple renewed their wedding vows in a ceremony on Mt. Tamalpias in Marin County. After years of hardship and separation, Eileen, Bob and Parker lived together as a family in a small apartment in Fairfax. Parker attended Sir Francis Drake High School and Bob often made him lunch, which he would bring to him at school. “That was the longest we ever stayed together that I could remember,” Parker said in a 1991 interview. “It was tough at first but we worked out and it was alright. My dad and I got buddy buddy. We watched football games together. It was my mom, me and my dad. It was great. I wish it could have continued.”

But it didn’t last. After about eight months, Bob returned to San Francisco where he lived until his death from emphysema in 1986.

During the 1980s, Eileen wrote an unpublished autobiography Who Wouldn’t Walk With Tigers. Passages of the biography have been printed in numerous articles and books such as Brenda Knight’s 1996 Women of the Beat Generation, but unfortunately, as of Eileen’s death, the manuscript was missing.

Through the decades, Eileen maintained a close relationship with Bob and always championed his poetry. She collaborated on two subsequent publications of his work and in 1980 presented a collection of Bob’s poetry to the Bibliotec Archives at the Sorbonne in Paris. Much of the work she transcribed, she contributed to the Mugar Museum and Library at Boston University. “Eileen was a very frail person, but she had an extraordinary inner strength,” Foye said. “I have an image of Eileen sitting in cafes with Bob’s work right there with her. She had total dedication… She had no doubt about how great his poetry was.”

In the final years of her life, Eileen moved to the East Bay living in Berkeley, El Cerrito and Richmond. She is survived by her son Parker and daughter Lisa.

A memorial will be held for Eileen at 7 p.m., on Feb. 18th at Specs Bar, 12 William Saroyan Pl in San Francisco. Bring poetry and food. Any contributions for Eileen’s funeral expenses should be made out to Robert Parker Kaufman. For further information, please contact John Geluardi at jgeluardi@gmail.com.